Volume Size

In this section, you’ll have a better understanding of concepts related to volume size.

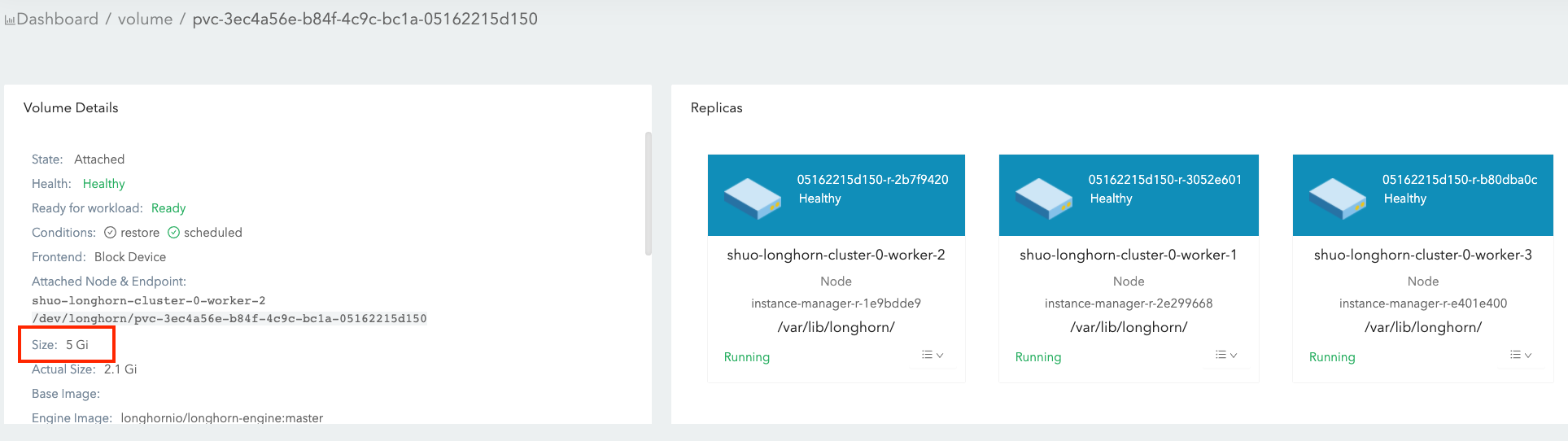

Volume Size:

- It is what you set during the volume creation, and we will call it nominal size in this doc to avoid ambiguity.

- Since the volume itself is just a CRD object in Kubernetes and the data is stored in each replica, this is actually the nominal size of each replica.

- The reason we call this field as “nominal size” is that Longhorn replicas are using sparse files to store data and this value is the apparent size of the sparse files (the maximum size to which they may expand). The actual size used by each replica is not equal to this nominal size.

- Based on this nominal size, the replicas will be scheduled to those nodes that have enough allocatable space during the volume creation. (See this doc for more info about node allocation size.)

- The value of nominal size determines the max available space when the volume is in use. In other words, the current active data size hold by a volume cannot be greater than its nominal size.

Volume Actual Size

- The actual size indicates the actual space used by each replica on the corresponding node.

- Since all historical data stored in the snapshots and active data will be calculated into the actual size, the final value can be greater than the nominal size.

- The actual size will be shown only when the volume is running.

Example

In the example, we will explain how volume size and actual size get changed after a bunch of IO and snapshot related operations.

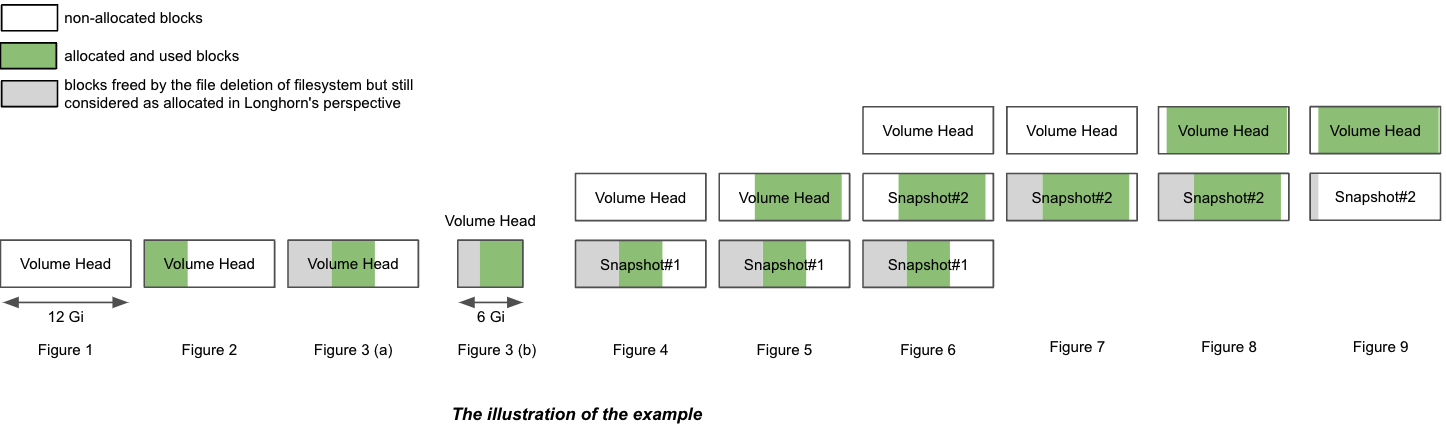

The illustration presents the file organization of one replica. The volume head and snapshots are actually sparse files, which we mentioned above.

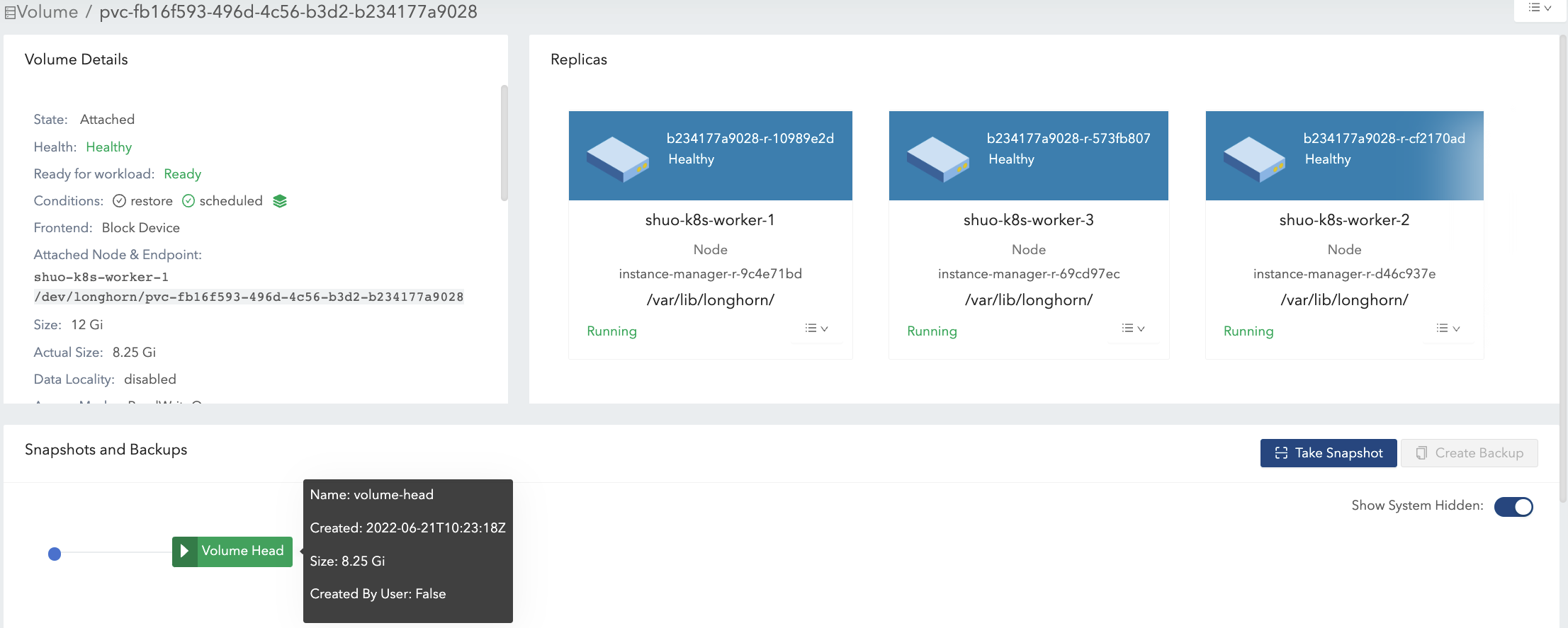

- Create a 12 Gi volume with a single replica, then attach and mount it on a node. See Figure 1 of the illustration.

- For the empty volume, the nominal

sizeis 12 Gi and theactual sizeis almost 0. - There is some meta info in the volume hence the

actual sizeis 260 Mi and is not exactly 0.

- For the empty volume, the nominal

- Write 4 Gi data (data#0) in the volume mount point. The

actual sizeis increased by 4 Gi because of the allocated blocks in the replica for the 4 Gi data. Meanwhile,dfcommand in the filesystem also shows the 4 Gi used space. See Figure 2 of the illustration.

Delete the 4 Gi data. Then,

dfcommand shows that the used space of the filesystem is nearly 0, but theactual sizeis unchanged.Users can see the volume

actual sizeis not shrunk after deleting the 4 Gi data. Longhorn is a block-level storage system. Therefore, the deletion in the filesystem only marks the blocks that belong to the deleted file as unused. Currently, Longhorn does not support TRIM/UNMAP operations, so thediscardmount option orfstrimin the filesystem layer cannot reclaim the unused blocks. In consequence, the actual size of Longhorn volumes cannot be shrunk in this case.

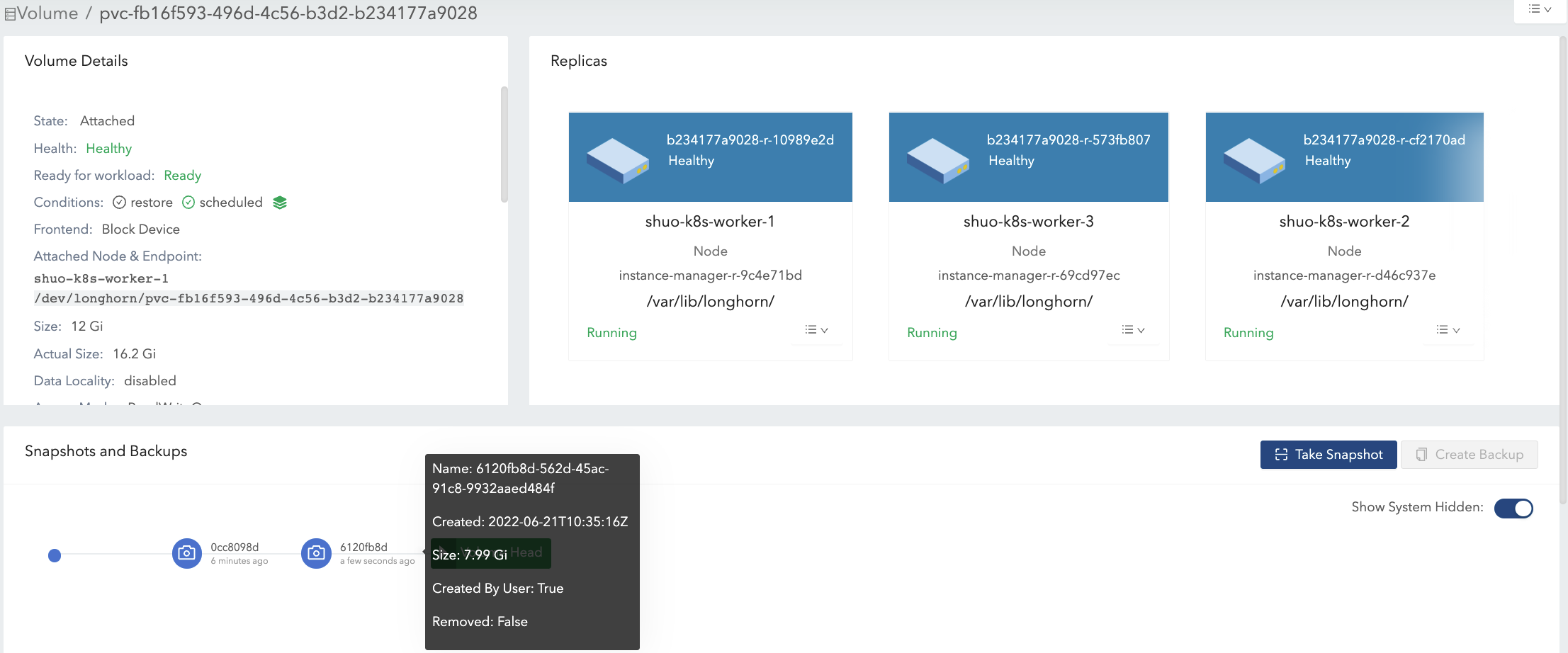

Then, rewrite the 4 Gi data (data#1), and the

dfcommand in the filesystem shows 4 Gi used space again. However, theactual sizeis increased by 4 Gi and becomes 8.25Gi. See Figure 3(a) of the illustration.After deletion, filesystem may or maynot reuse the recently freed blocks from recently deleted files according to the filesystem design and please refer to Block allocation strategies of various filesystems. If the volume nominal

sizeis 12 Gi, theactual sizein the end would range from 4 Gi to 8 Gi since the filesystem may or maynot reuse the freed blocks. On the other hand, if the volume nominalsizeis 6 Gi, theactual sizeat the end would range from 4 Gi to 6 Gi, because the filesystem has to reuse the freed blocks in the 2nd round of writing. See Figure 3(b) of the illustration.Thus, allocating an appropriate nominal

sizefor a volume that holds heavy writing tasks according to the IO pattern would make disk space usage more efficient.

- Take a snapshot (snapshot#1). See Figure 4 of the illustration.

- Now data#1 is stored in snapshot#1.

- The new volume head size is almost 0.

- With the volume head and the snapshot included, the

actual sizeremains 8.25 Gi.

Delete data#1 from the mount point.

- The data#1 filesystem level removal info is stored in current volume head file. For snapshot#1, data#1 is still retained as the historical data.

- The

actual sizeis still 8.25 Gi.

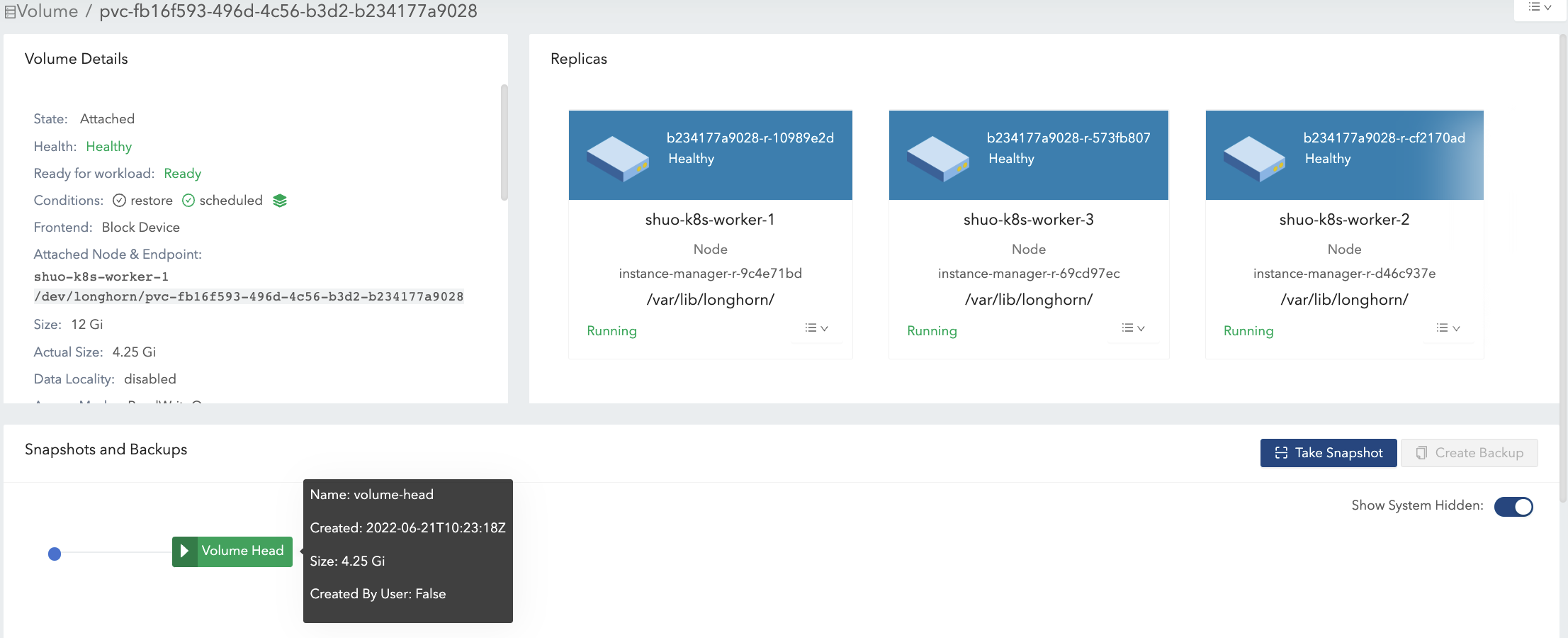

Write 8 Gi data (data#2) in the volume mount, then take one more snapshot (snapshot#2). See Figure 5 of the illustration.

- Now the

actual sizeis 16.2 Gi, which is greater than the volume nominalsize. - From a filesystem’s perspective, the overlapping part between the two snapshots is considered as the blocks that have to be reused or overwritten. But in terms of Longhorn, these blocks are actually fresh ones held in another snapshot/volume head. See the 2 snapshots in Figure 6.

The volume head holds the latest data of the volume only, while each snapshot may store historical data as well as active data, which consumes at most size space. Therefore, the volume

actual size, which is the size sum of the volume head and all snapshots, is possibly bigger than the size specified by users.Even if users will not take snapshots for volumes, there are operations like rebuilding, expansion, or backing up that would lead to system (hidden) snapshot creation. As a result, volume

actual sizebeing larger than size is unavoidable under some use cases.- Now the

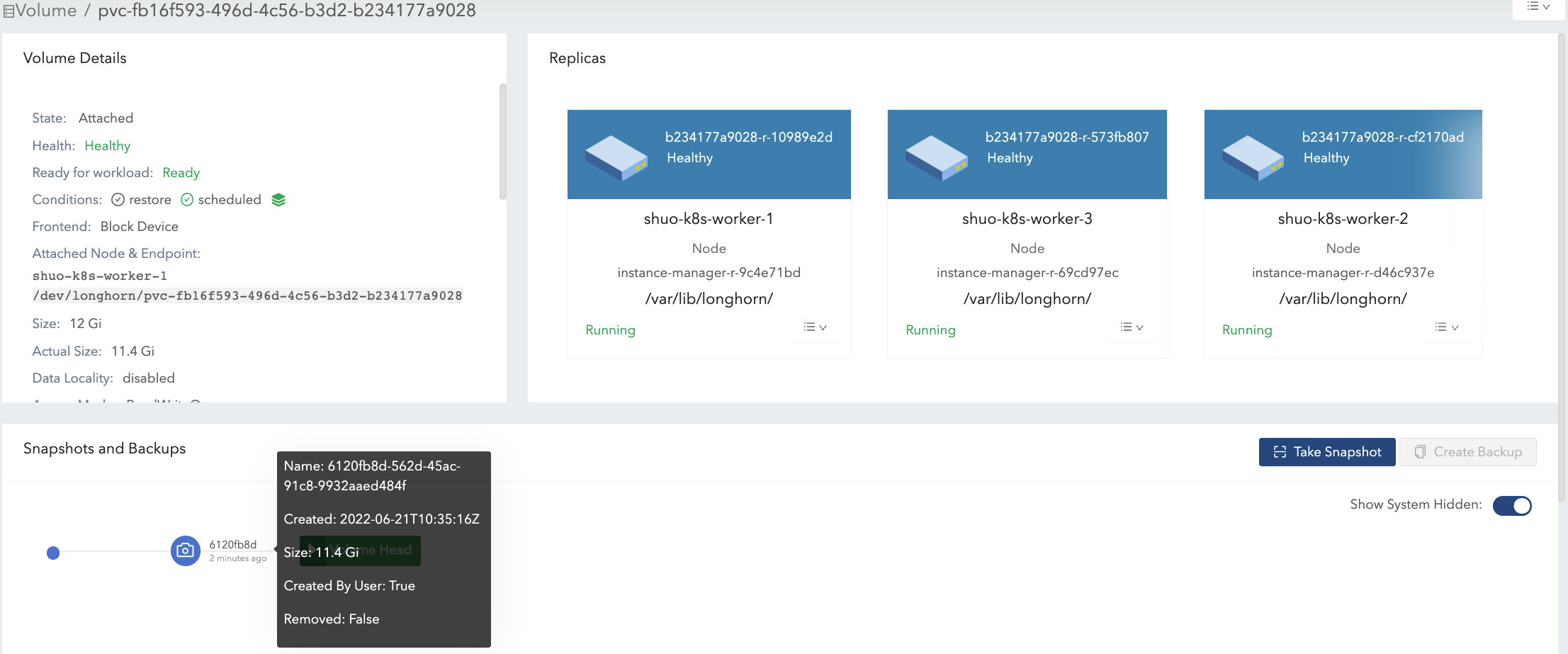

- Delete snapshot#1 and wait for snapshot purge complete. See Figure 7 of the illustration.

- Here Longhorn actually coalesces the snapshot#1 with the snapshot#2.

- For the overlapping part during coalescing, the newer data (data#2) will be retained in the blocks. Then some historical data is removed and the volume gets shrunk (from 16.2 Gi to 11.4 Gi in the example).

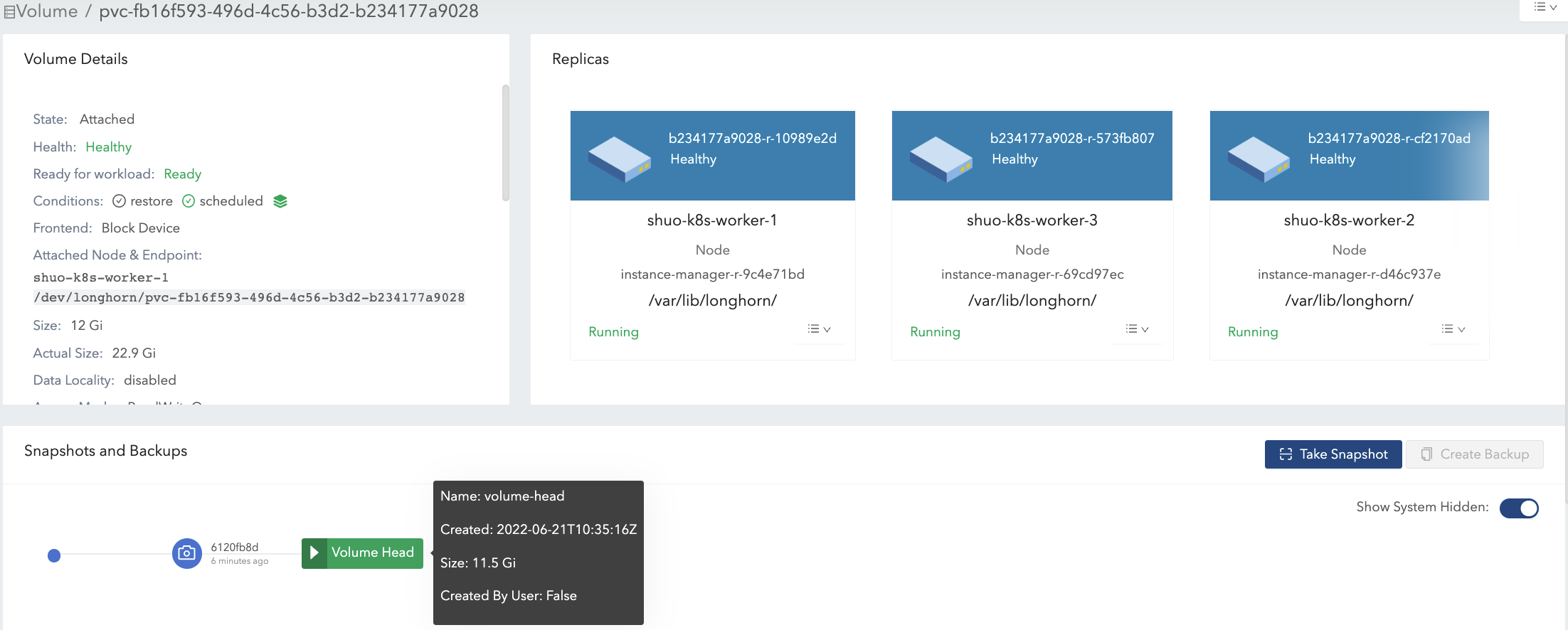

- Delete all existing data (data#2) and write 11.5 Gi data (data#3) in the volume mount. See Figure 8 of the illustration.

- this makes the volume head actual size becomes 11.5 Gi and the volume total actual size becomes 22.9 Gi.

- Try to delete the only snapshot (snapshot#2) of the volume. See Figure 9 of the illustration.

- The snapshot directly behinds the volume head cannot be cleaned up. If users try to delete this kind of snapshot, Longhorn will mark the snapshot as Removing, hide it, then try to free the overlapping part between the volume head and the snapshot for the snapshot file. The last operation is called snapshot prune in Longhorn and is available since v1.3.0.

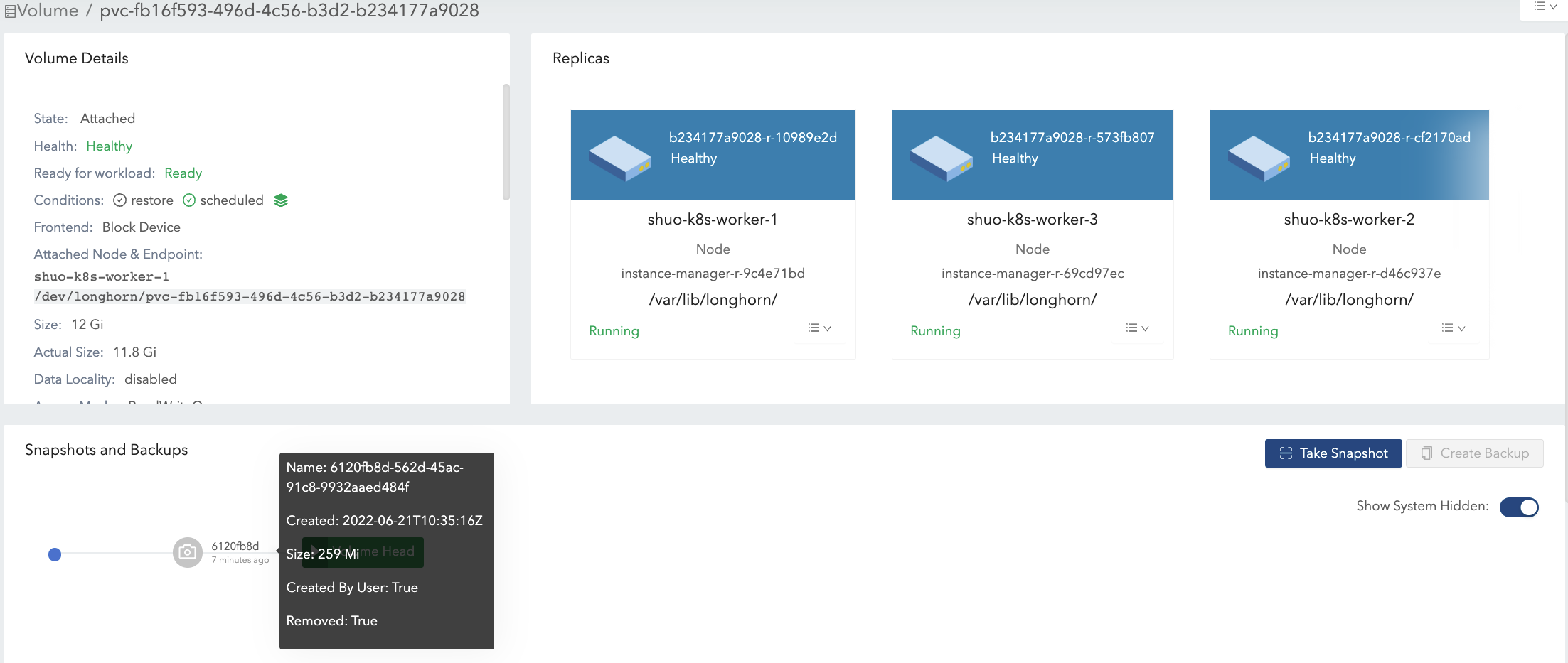

- Since in the example both the snapshot and the volume head use up most of the nominal space, the overlapping part almost equals to the snapshot actual size. After the pruning, the snapshot actual size is down to 259 Mi and the volume gets shrunk from 22.9 Gi to 11.8 Gi.

Here we summarize the important things related to disk space usage we have in the example:

Unused blocks are not released

Longhorn does not support TRIM/UNMAP operations. Hence deleting files from filesystems will not lead to volume actual size decreasing/shrinking.

Allocated blocks but unused are not reused

Deleting then writing new files would lead to the actual size keeps increasing. Since the filesystem may not reuse the recently freed blocks from recently deleted files. Thus, allocating an appropriate nominal size for a volume that holds heavy writing tasks according to the IO pattern would make disk space usage more efficient.

By deleting snapshots, the overlapping part of the used blocks might be eliminated regardless of whether the blocks are recently released blocks by the filesystem or still contain historical data.

Space Configuration Suggestions for Volumes

Reserve enough free space in disks as buffers in case of the actual size of existing volumes keep growing up.

A general estimation for the maximum space consumption of a volume is

(N + 1) x head/snapshot average actual size- where

Nis the total number of snapshots the volume contains (including the volume head), and the extra1is for the temporary space that may be required by snapshot deletion. - The average actual size of the snapshots varies and depends on the use cases.

If snapshots are created periodically for a volume (e.g. by relying on snapshot recurring jobs), the average value would be the average modified data size for the volume in the snapshot creation interval.

If there are heavy writing tasks for volumes, the head/snapshot average actual size would be volume the nominal size. In this case, it’s better to set

Storage Over Provisioning Percentageto be smaller than 100% to avoid disk space exhaustion. - Some extended cases:

There is one snapshot recurring job with retention number is

N. Then the formula can be extended to:(M + N + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1) x head/snapshot average actual size- The explanation of the formula:

Mis the snapshots created by users manually. Recurring jobs are not responsible for removing this kind of snapshot. They can be deleted by users only.Nis the snapshot recurring job retain number.- The 1st

1means the volume head. - The 2nd

1means the extra snapshot created by the recurring job. Since the recurring job always creates a new snapshot then deletes the oldest snapshot when the current snapshots created by itself exceeds the retention number. Before the deletion starts, there is one extra snapshot that can take extra disk space. - The 3rd

1is the system snapshot. If the rebuilding is triggered or the expansion is issued, Longhorn will create a system snapshot before starting the operations. And this system snapshot may not be able to get cleaned up immediately. - The 4th

1is for the temporary space that may be required by snapshot deletion/purge.

- The explanation of the formula:

Users don’t want snapshot at all. Neither (manually created) snapshot nor recurring job will be launched. Assume setting Automatically Cleanup System Generated Snapshot is enabled, then formula would become:

(1 + 1 + 1) x head/snapshot average actual size- The worst case that leads to so much space usage:

- At some point the 1st rebuilding/expansion is triggered, which leads to the 1st system snapshot creation.

- The purges before and after the 1st rebuilding does nothing.

- There is data written to the new volume head, and the 2nd rebuilding/expansion somehow is triggered.

- The snapshot purge before the 2nd rebuilding may lead to the shrink of the 1st system snapshot.

- Then the 2nd system snapshot is created and the rebuilding is started.

- After the rebuilding done, the subsequent snapshot purge would lead to the coalescing of the 2 system snapshots. This coalescing requires temporary space.

- During the afterward snapshot purging for the 2nd rebuilding, there is more data written to the new volume head.

- At some point the 1st rebuilding/expansion is triggered, which leads to the 1st system snapshot creation.

- The explanation of the formula:

- The 1st

1means the volume head. - The 2nd

1is the second system snapshot mentioned in the worst case. - The 3rd

1is for the temporary space that may be required by the 2 system snapshot purge/coalescing.

- The 1st

- The worst case that leads to so much space usage:

- where

Do not retain too many snapshots for the volumes.

Cleaning up snapshots will help reclaim disk space. There are two ways to clean up snapshots:

- Delete the snapshots manually via Longhorn UI.

- Set a snapshot recurring job with retention 1, then the snapshots will be cleaned up automatically.

Also, notice that the extra space, up to volume nominal

size, is required during snapshot cleanup and merge.An appropriate the volume nominal

sizeaccording to the workloads.

© 2019-2025 Longhorn Authors | Documentation Distributed under CC-BY-4.0

© 2025 The Linux Foundation. All rights reserved. The Linux Foundation has registered trademarks and uses trademarks. For a list of trademarks of The Linux Foundation, please see our Trademark Usage page.